Of Course, US Actions May Facilitate China’s Advance in Latin America

In the March 27, 2025 Foreign Policy article, «China Won’t Be the Obvious Winner in Latin America,” Ryan Berg argues against a “narrative” that he sees emerging, including from myself, that certain actions by the current U.S. Administration may inadvertently facilitate China’s advance in Latin America, among other adverse consequences to U.S. interests.

As the “former staffer” Berg refers to, I appreciate the irony of the argument. In my role on Secretary of State Michael Pompeo’s Policy Planning staff (S/P), including responsibilities for Western Hemisphere Affairs (WHA) and International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL), I saw first-hand the effort of the enormously talented group in engagements, messaging, and other activities pushing back against the advance of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the Western Hemisphere. I see similar efforts, talent and dedication by current Secretary of State Marco Rubio and his team at State in pushing back against China’s even more significant incursions in the hemisphere today.

The four arguments made by Berg against the China advance narrative

Berg advances four groups of arguments for why concerns about China’s advance may be overblown: (1) economic and diplomatic “headwinds” that may limit China’s progress; (2) initiatives such as an expanded Development Finance Corporation (3) “red lines” that cause hesitation by both the PRC and its Latin American partners, and (4) the “multi-aligned” character of the region in which it resists dichotomous choices between the U.S. and the PRC.

China’s economic troubles have not slowed its advance in key sectors such as telecommunications, energy, and strategic minerals.

China’s economic troubles aren’t stopping its advance in strategic sectors

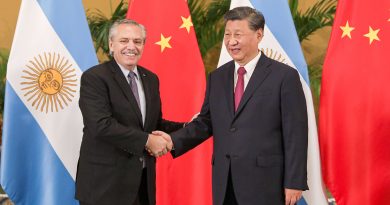

Berg is correct that the PRC economy faces significant problems and structural contradictions that hamper its growth, and to some degree, limit policy bank lending for large-scale foreign projects such as those tied to the “Belt and Road Initiative.” Unfortunately, those problems have not restrained the significant advance of PRC activities in some of the most strategically sensitive sectors in Latin America, including a growing dominance of the digital infrastructure in the region such as in telecommunications, cloud computing, and security systems. Nor has it restrained the increasing role by PRC-based companies in renewable energy including electric vehicles (EVs), solar, wind and hydroelectric energy generation and transmission, including control of 57% of Chile’s electricity transmission infrastructure, as well as 100% of transmission in the greater Lima, Peru region. Nor have China’s economic problems prevented PRC-based companies from locking up substantial portions of strategic minerals supply chains in the region, including niobium in Brazil and lithium in Argentina, Chile and Bolivia. Nor have they restrained the PRC advance in the space sector, including not only the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)-operated Deep Space Radar in Argentina, but also the possible PRC construction of a new 40-meter radiotelescope in San Juan, Argentina and the proposed Ventarrones PRC space facility in Chile. Nor did China’s economic constraints keep PRC logistics giant COSCO from moving forward with its $3.5 billion megaport in Chancay, Peru over which it has exclusive control.

The shift in Chinese lending reflects greater economic sophistication

Berg rightly notes that lending to the region from China’s two principal policy banks, China Development Bank and China Import-Export Bank, has fallen off in recent years. This shift, commonly noted by those seeking to downplay China’s advance, actually reflects the worrisome increase in sophistication of PRC economic engagement toward a greater use of commercial and other internal financing mechanisms. Moreover, PRC advances in strategic industries such as telecommunications, other digital sectors, EVs, and energy infrastructure are driven by its ability to dominate markets and generate revenue rather than to generate large government-to-government loans for economically questionable megaprojects that once characterized PRC “Belt and Road” projects in Africa, Central Asia, and elsewhere.

Regional distrust of China coexists with the pursuit of benefits

In the political domain, Berg rightly notes mistrust in Latin America, as elsewhere, toward China as a political and business partner. Yet such awareness of the dangers of China have always coexisted in the region with the hopes of benefitting from engaging with it politically, commercially, or personally. Berg does not explain how that mistrust will limit China’s advance now when it has not done so in the past, particularly at a time in which the US government is arguably tarnishing the attractiveness of the U.S. as a partner by suggesting the possibility of military action against neighbors such as Panama and Mexico, imposing tariffs against virtually all of the region, expelling migrants, and retaliating against those such as the Petro administration in Colombia who don’t accept them.

The DFC is not enough to counter China in the region

Berg’s second argument is that the current administration’s initiatives such as expansion of the Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and reducing restrictions on which countries and in which sectors DFC can help will provide U.S. private sector alternatives to Chinese loans, and thus, indirectly limit China’s advance. While the DFC is indeed an important tool whose use should be expanded, the reality is that channeling private-sector capital into countries characterized by corruption, violence, political risk and other uncertainties is like herding cats. Even where successful, such investment may only complement, or even facilitate that of the PRC, rather than keep it out.

Another problem with trying to leverage the U.S. private sector to keep China out of Latin America is that the Administration’s focus on tariffs to incentivize investors to build their supply chains in the U.S. directly contradicts using DFC and other tools to induce them to invest elsewhere. In addition, the uncertainties created by rapidly changing tariff levels and possible retaliation decrease incentives for companies to invest anywhere. In addition, when U.S. partners such as Japan, Korea, and the European Union are subjected to increased tariffs, it may decrease their interest in collaborating with the United States to provide alternatives to Chinese initiatives in Latin America.

U.S. tariff threats and confrontational rhetoric may be pushing the region toward China’s orbit.

U.S. “red lines” do not effectively deter China

Berg’s third argument is that current administration «red lines” will have a deterrent effect on China’s advance. To date, the its pressure has secured some accomplishments such as Panama’s withdrawal from the Belt and Road initiative. The short-lived Administration “win” with Hong Kong-based Hutchison’s selloff of $23 billion in port assets to Blackrock was undone by PRC pressure. In the tariff war, the PRC’s retaliatory increase of tariffs against U.S. products, suspension of aircraft imports from Boeing, implementation of export licensing on rare earth metals, and declared intent to “fight to the end” all suggest that China will not respect U.S. “red lines.”

Regional multi-alignment facilitates China’s advance

Berg’s final argument is that Latin American partners do not actually seek to choose between the U.S. and PRC, but rather, are «multi-aligned.» While correct, this truth is actually one of the factors facilitating China’s advance. In the face of U.S. threats of tariffs and other deleterious actions, Latin American states are likely to counterbalance through a combination of new partnerships with the PRC, the EU, Asia and other actors rather than bandwagon with the U.S. Doing so makes them less susceptible to U.S. pressure, and they will feel freer to buy often cheaper Chinese digital products, accept contracts and investments by its companies, or cooperate with the PRC in space and security affairs.

The dismantling of institutions and lack of investment undermine the U.S. position

The most compelling part of Berg’s article is, ironically, the conclusion, where he emphasizes the importance of the current administration choices in replacing dismantled State Department, USAID and other programs with more effective ones. Unfortunately, the list of shuttered activities without successor organizations continues to grow: the Voice of America, the U.S. Institute for Peace, the Woodrow Wilson Institute, and a possible halving of the State Department budget that would eliminate the National Endowment for Democracy and countless others. This, when combined with statements by the President that may be interpreted negatively by allies and the Administration’s instruction not to enforce the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, may be interpreted by some U.S. partners as indications thatAdministration does not significantly value, or is not disposed to invest in, goodwill and trust in the U.S., democratic values, and institutional frameworks as key resources in the struggle against China. The resulting reliance on transactionalism puts the US at a grave disadvantage in a fight against a PRC possessing all of the instruments of state control over its political system and economy, whereas the US has a predominantly market-oriented system of limited government that cannot be wielded as a weapon of the state in the same way that the PRC can wield its economy. Discounting the risk of China’s advance in Latin America in that context carries grave risks for the U.S. and the region.